“The Indian must conform to the ‘white man’s ways,’ peaceably if they will forcibly if they must.” Thomas Jefferson Morgan, Commissioner of Indian Affairs

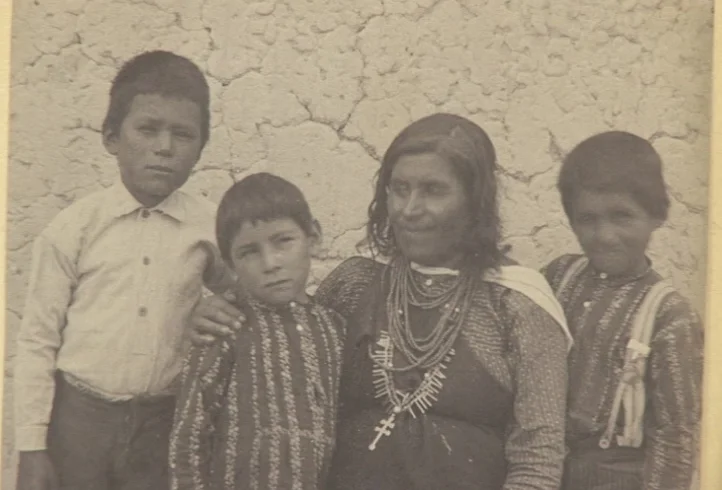

In 1892, the small Indian Pueblo of Isleta, 10 miles south of Albuquerque, filed a writ of habeas corpus against the federally run Albuquerque Indian Boarding School. For three years, the School held 15 children without parental permission and without family contact. This law suit threatened the entire boarding school model. The Indians called these children “Los Cautivos,” the Captives.

During the 1880’s as the Indian Wars were winding down the US was confronted with the “Indian Question;” What to do with the 250,000 Native Americans living in the West? The answer was posed as a choice between annihilation or assimilation. Hardliners proposed complete eradication of Native peoples. Reformers, like the Indian Rights Association (IRA) believed that the Christian alternative was assimilation through education. The Carlisle Indian School, founded by Richard Henry Pratt in 1879, was adopted as a model of assimilation.

“A majority of Indian children must be placed, at a tender age, in reservation boarding schools and be kept there until contact with civilized ways of life had made them members of a civilized society.” Thomas Jefferson Morgan, Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

Winning the election of 1888, Benjamin Harrison quickly advanced an aggressive policy of forced Indian education, opening new boarding schools and taking over those run by religious organizations. He appointed a number of IRA reformers to significant positions such as Thomas Jefferson Morgan, Commissioner of Indian Affairs and Daniel Dorchester, Superintendent of Indian Education.

William Creager was an IRA reformer and headmaster of the Albuquerque Indian Boarding School. The Albuquerque school, like all federally run schools was funded through Congress and monies were dependent upon enrollment. The more students, the more money. Creager was afraid of letting children go home for holidays or summer vacation as they may not return to school. His solution was to keep the children, never allow them to go home.

Juan Rey and Pita Abeita had three sons at the Albuquerque school. Four-year-old Luis accompanied his brothers just to visit and was expected to return within a day or two. But Creager kept Luis. When Juan Rey tried to retrieve his youngest boy, he was beaten and threatened with worse should he return.

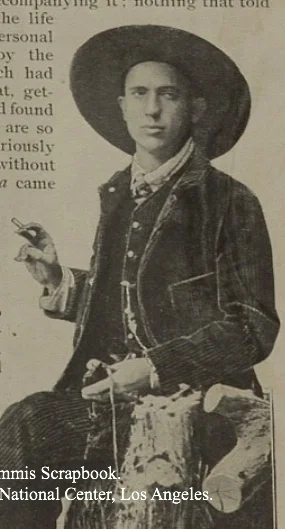

Charles Fletcher Lummis was a popular author, journalist, photograper and archaeologist. He lived with Pita and Juan Rey Abeita and experienced first hand the suffering of his friends.

Writing for the national newspapers and magazines, Lummis opposed the federal boarding school system, questioned the authority of the “superior race,” and sought to change public opinion on Indians.

“Indians have the right to live as Indians.” Charles Fletcher Lummis

Isleta and other Pueblos quickly refused to send their children to the government run schools, hiding their children during official sweeps, or enrolling them in the more lenient Catholic boarding schools. This action undermined the successful operation of the Federal schools by limiting the Congressional funding.

In 1890, the Carlisle Indian School graduated it’s first class. Among the graduates was Henry Kendall, the son of Vincente Jiron, a past Governor of Isleta who held strong, traditional beliefs. Kendall had been at school for 11 years and his letters during that period show him to be the exemplar of the boarding school education. He returned to Isleta fired with a missionary zeal to transform his neighbors into accepting the “American Way.” He immediately became an informer to Headmaster Creager and the Federal government on Isletan plans to counter the forced education policies.

A third summer arrived and still no contact with their children. The Pueblo had had enough. A council was called and Lummis was asked his opinion. He suggested filing a writ of habeas corpus against the Albuquerque school on behalf of the three Abeita boys.

The filing of the writ raised alarms from Albuquerque to Washington D.C. Confronted with the possibility of a precedent setting legal decision with national implications, Commissioner Morgan instructed Principal Creager to ensure the case never went to court. The night before the case was to be heard, Creager sent school guards to intimidate Juan Rey Abeita. He didn’t count on the pugnacious Lummis who stood down Creager’s thugs.

The next morning Creager sent a message to the Pueblo’s lawyer stating that he was ready to reach an agreement. All fifteen children were returned to their families that afternoon.

In newspaper articles across the nation, Lummis recounted the emotional homecoming. Especially poignant was the reunion of Pita Abeita and seven year-old Luis. Upon his return, Lummis noted, mother could not talk to her son, as Luis had lost his language and could speak only English. Lummis’ wife Eva, had to act as translator.

“And Pita — as fine and motherly a woman as I ever knew—cried; and Luis cried; and so I think did we all.” Charles F. Lummis

Later that year Congress passed a bill that required that boarding schools could only take Indian children with the permission of their parents. By 1893 Commissioner Morgan was replaced by D. M Browning.

“Even superstitious and backwards people have a right to their children.” D.M. Browning, Commissioner of Indian Affairs 1893

Although this was a positive outcome for the Pueblos of New Mexico, it had no effect on other tribes. The government obtain parental permission through threats, intimidation and the withholding of Treaty mandated annuities.

The Pueblos continued to move their children from one boarding school to another, favoring those schools which offered the best care and curriculums. Over the decades the New Mexico boarding schools, in many ways, became an extension of Pueblo culture.

Forty years later, in 1928, the government released the Meriam Report, a survery of Federal Indian Policy spanning 80 years. The Report found that the care of “Indian children to be grossly inadequate.” The findings substantiated the complaints of the Pueblos and the critiques articulated by Lummis. Unfortunately, the assimilationist policies continued until the 1970s.